10 ways The Hunger Games is our present – and our future. #3: “District 12, where you can starve to death in safety”

How The Hunger Games reflects inequality and economic segregation in our world

This is a series of blog posts based on my new book, Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games, published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books.

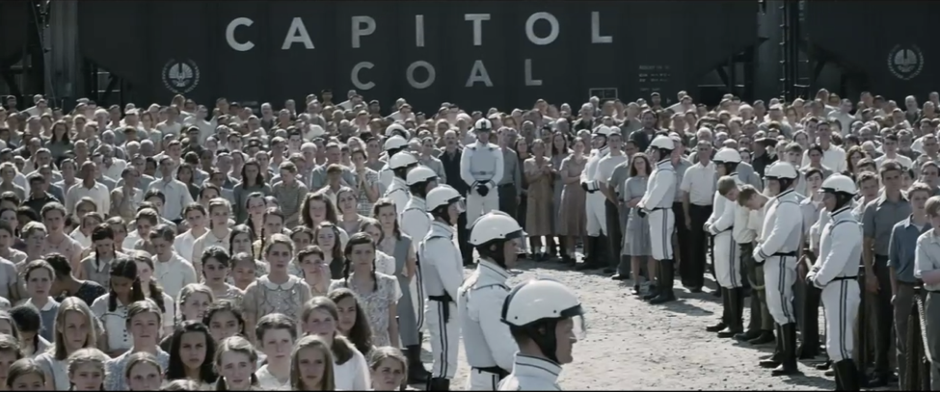

Panem consists of the wealthy ruling Capitol city, located in the Rocky Mountains, surrounded by 12 (originally 13) poorer districts. Katniss’ District 12 is located in today’s Appalachia. The furthest from the Capitol, it specializes in coal mining.

The government is a dictatorship, a surveillance state in which the districts are forced into subservience to the Capitol, expected to provide goods in exchange for ‘protection,’ for peace and prosperity. But only the Capitol is lavishly rich and technologically advanced, while the districts survive in poverty and distress.

The Hunger Games, the first book, was released on 14 September 2008, the same day investment bank Lehman Brothers declared bankruptcy and the global financial crisis entered its most acute phase. This was an accident of timing but also, for a series that depicts a world of gross inequality and elite corruption, deliberately prescient. The crisis was in many ways the outcome of inequality; the only way ordinary people could afford a home was courtesy of fundamentally fake financial instruments, based on income they didn’t have and interest rates they couldn’t afford.

So why didn’t the crisis provoke a widespread revolt against the system? Supported by its propagandists, the Capitol was said to have ‘won’ the story regarding the causes of the crisis and its required consequences: that the rich need to be protected while the poor are punished. It was class war, by the rich, on the poor, as blatant as the cruel regime of the fictional Capitol.

The Hunger Games isn’t just the brutally honest name of the annual fight-to-the-death competition organized by the Capitol, the city that dominates Panem. It’s the way that its elite controls the districts. Starvation, scarcity and minimal rewards doled out to subservient districts; the Capitol uses hunger as a weapon against the masses. It’s also a powerful metaphor for the economic system we live under today, so much so that ‘the Hunger Games’ has now become shorthand for any especially brutally competitive environment or economy.

It might seem horribly honest for a regime to call its primary propaganda tool the ‘Hunger Games’. But it’s entirely deliberate. As Suzanne Collins has said, “The socio-political overtones of The Hunger Games were very intentionally created to characterize current and past world events, including the use of hunger as a weapon to control populations.”

The Games are a reminder, a threat and a demonstration of domination. Naming them is about power. It’s not meant to generate support for the system, but to crush any humane alternative. As Katniss recognizes, it’s the Capitol’s way of saying, “Look how we take your children and sacrifice them and there’s nothing you can do.” You can’t even protest, let alone rebel.

The thing is, how the Capitol justifies its regime is really not so different from how some people promote capitalism in our world: how it disciplines us to work or starve, punishes the ‘indolent’ and rewards the ‘winners.’ If we think the Capitol is too honest, we forget how in our world apologists for capitalism also celebrate its cruel and controlling methods.

Immiseration and unemployment are a deliberate political strategy of capitalism. Scarcity induces fear, of not being able to survive, but also of each other. In survival, we put ourselves and our families over the possibility of solidarity and social change.

Katniss describes how starvation is normal in her district, but it’s never an official cause of death. We look away too, but in the richest country on earth, widespread hunger is real. Nearly 49 million Americans, including more than 16 million children, live in households that lack food. More children are hungry than adults: 1 in 5 go hungry at some point during any year.

In the United States, hunger was virtually eliminated in the 1970s. Now, after 40 years of a right-wing economic regime, it’s back. The number of people going hungry has grown dramatically. The present levels represent a fivefold rise since the late 1960s, with an increase of 57 percent since the late 1990s alone.

Hunger is particularly prevalent in the districts. A total of 15 percent of families living in rural areas experience food insecurity. People of color are also disproportionately affected. Black and Latino children experience hunger at double the rate of white children.

Conservatives attack such statistics, claiming that this can’t possibly be true in such a rich country. It probably feels that way from the full tables of the Capitol.

Katniss’s District 12 is in Appalachia, one of the most deprived regions in the US, and one of the most maligned. Suzanne Collins chose it for a reason: it’s looked down on as irredeemably poor and backward, ignorant and violent. The Hunger Games also illustrates how we shame the poor. Classism is the last acceptable form of discrimination. It normalizes poverty, because the poor are assumed to be lazy and irresponsible. In fact, their poverty is created by the Capitol, by its heavily policed economic system and class division, then they’re blamed for their ‘dysfunction’ when it’s the system that’s responsible.

Further, in the world of The Hunger Games, the meagre tesserae system of food rationing offered by the Capitol to starving families – which comes at the cost of a higher chance of being selected for the Hunger Games – echoes our own punitive welfare systems. Not only are such benefits often insufficient to live on, they also come at a cost, to punish the poor with time-wasting, bureaucratic requirements to find low paid, insecure work. Such punitive ‘welfare’ rests on an engineered division which dates back centuries between the deserving ‘respectable working class’ and the undeserving ‘underclass.’ We’ll ignore for the moment that the most feckless residents of Panem reside in its Capitol. But they are the subject of the next post.

Of course, in contrast to the Capitol’s propaganda, in The Hunger Games we’re presented with different personification of the underclass. Katniss is decent, strong, brave and kind. She’s an honest working-class woman who suffers incredible hardship but endures. She might seem passive and resigned, but she’s also decisive and acts swiftly.

And as we, and Katniss, will discover, she’s not alone.

Stay Alive: Surviving Capitalism’s Coming Hunger Games is published in April/May 2021 by Zero Books and can be pre-ordered from the following places now: